BONLAB BLOG

Thoughts

&

Scientific Fiction

Autonomous electricity-free "icy road" warning signs

We set out to develop a prototype for “icy road” warning signs which was able to operate autonomously without the use of electricity, and which could be easily placed onto existing road features, such as street boundary pillars and road safety barriers.

The number of road accidents in the UK under frosty or icy conditions runs in the thousands. Our concept would aid to reduce these numbers, without the introduction of a digital, and thus electric, infrastructure.

The results from our studies are now published open access in the Journal of Materials Chemistry C from the Royal Society of Chemistry. The conceptual road sign application is a multi-lamellar flexible strip.

We set out to develop a prototype for “icy road” warning signs which was able to operate autonomously without the use of electricity, and which could be easily placed onto existing road features, such as street boundary pillars and road safety barriers.

The number of road accidents in the UK under frosty or icy conditions runs in the thousands. Our concept would aid to reduce these numbers, without the introduction of a digital, and thus electric, infrastructure.

The results from our studies are now published open access in the Journal of Materials Chemistry C from the Royal Society of Chemistry. The conceptual road sign application is a multi-lamellar flexible strip.

A temperature triggered response in the form of an upper critical solution temperature (UCST) type phase separation targeted near the freezing point of water manifests itself through light scattering as a clear-to-opaque transition. It is simultaneously amplified by an enhanced photoluminescence effect. The essence is summed up in the supporting video.

The active layer in the strip is a polystyrene-based solution. When the temperature drops to near freezing the polymer molecules undergo a phase transition, from a coil happily dissolved, into a globule that crashes out of solution. This crashing out (phase separation) triggers the transparent active layer to become cloudy white, and thus opaque. The temperature at which this occurs is referred to as the cloud point. It is the result of the scattering of light caused by the different refractive indices of the two phases.

The clear-to-opaque transition of the active layer on the black strip allows us to introduce colour, either by adding a dye dissolved in the plasticizer liquid, or by printing a coloured translucent image on the top layer of the strip. This effect is shown in the image below where Pac-Man’s ghost only appear under freezing conditions.

Road sign displaying full colour temperature response by adding oil blue, rose bengal, and 4-phenylazopheonl dyes to polystyrene-DOP mixture. The patch was imaged at below, above and below phase separation temperature (freezing point of water), top, middle and bottom, respectively.

We wanted our road sign to be more visible in the dark. For this the concept of restricted motion enhanced photoluminescence, often referred to as aggregation-induced emission (AIE), was used. Polystyrene labelled with tetraphenylethylene (TPE) was used for this. The fluorescent tag emits light vividly under icy conditions, as the combination of phase separation, increased viscosity of the system, and lower temperatures restricts its motion and thus enhances its light emission (see video).

Prof. dr. ir. Stefan Bon says: “We worked on this project for a number of years, with a team of talented people which included undergraduate, master, and PhD students and research fellows. The project was co-led by Robert Young and Joshua Booth, who are shared first author on the paper. We are delighted with how it turned out, and are pleased that all is now published open access in the Journal of Materials Chemistry C. We hope that people are enthusiastic about the concept.”

The paper can be accessed from here:

https://doi.org/10.1039/D1TC01189H

BonLab makes hydrogel beads communicate

Hydrogels are soft objects that are mainly composed of water. The water is held together by a 3D cross-linked mesh. In our latest work we show that hydrogel beads made from the bio-sustainable polymer alginate can be loaded up with different types of molecules so that the beads can communicate via chemistry.

Chemical communication underpins a plethora of biological functions and behaviours. Plants, animals and insects rely on it for cooperative action, your body uses it to moderate its internal environment and your cells require it to survive.

A key goal of materials science is to mimic this biological behaviour, and synthetic objects that are able to communicate with one another by the sending and receiving of chemical messengers are of great interest at a range of length scales. The most widely explored platform for this kind of communication is between nanoparticles, and to a lesser extent, vesicles, but to date, very little work explores communication between large (millimetre-sized), soft objects, such as hydrogels.

In our work published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry B, we present combinations of large, soft hydrogel objects containing different signalling and receiving molecules, can exchange chemical signals. Beads encapsulating one of three species, namely the enzyme urease, the enzyme inhibitor silver (Ag+), or the Ag+ chelator dithiothreitol (DTT), are shown to interact when placed in contact with one another. By exploiting the interplay between the enzyme, its reversible inhibitor, and this inhibitor’s chelator, we demonstrate a series of ‘conversations’ between the beads.

Hydrogels are soft objects that are mainly composed of water. The water is held together by a 3D cross-linked mesh. In our latest work we show that hydrogel beads made from the bio-sustainable polymer alginate can be loaded up with different types of molecules so that the beads can communicate via chemistry.

Chemical communication underpins a plethora of biological functions and behaviours. Plants, animals and insects rely on it for cooperative action, your body uses it to moderate its internal environment and your cells require it to survive.

A key goal of materials science is to mimic this biological behaviour, and synthetic objects that are able to communicate with one another by the sending and receiving of chemical messengers are of great interest at a range of length scales. The most widely explored platform for this kind of communication is between nanoparticles, and to a lesser extent, vesicles, but to date, very little work explores communication between large (millimetre-sized), soft objects, such as hydrogels.

In our work published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry B, we present combinations of large, soft hydrogel objects containing different signalling and receiving molecules, can exchange chemical signals. Beads encapsulating one of three species, namely the enzyme urease, the enzyme inhibitor silver (Ag+), or the Ag+ chelator dithiothreitol (DTT), are shown to interact when placed in contact with one another. By exploiting the interplay between the enzyme, its reversible inhibitor, and this inhibitor’s chelator, we demonstrate a series of ‘conversations’ between the beads.

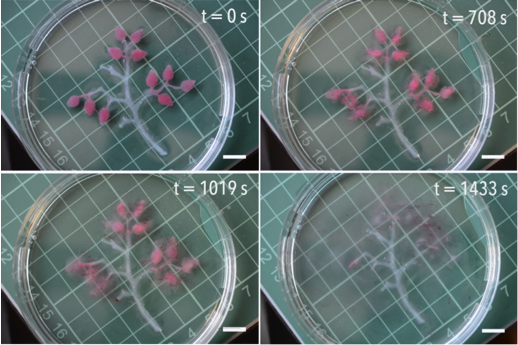

The movie shows two different scenario's:

Scenario 1: When a bead containing both urease, at a concentration of 5 g/L, and silver, at a concentration of 0.2 mmol/L, is immersed in a 0.1 mol/L solution of urea, no pH increase is observed (left bead). If an identical bead (middle bead) makes contact with one containing 0.52 mol/L DTT (right bead), the contained DTT diffuses into the silver-bound ‘enzyme’ bead. This results in the chelation of silver ions from the urease and thus its reactivation. Scale bar = 5 mm.

Scenario 2: a 1 mmol/L ‘silver’ bead sits next to a 0.125 g/L ‘urease’ bead (far left and the top middle bead, respectively) in an aqueous solution of 0.1 mol/L urea. In this case, however, a third bead is introduced, namely a 0.52 mol/L ‘DTT’ bead (bottom middle). The far-right bead, containing 0.125 g/L urease, undergoes its colour and pH change as expected (onset at 214 seconds). As the left-hand ‘enzyme’ bead makes contact with a ‘silver’ bead, a pH increase after this time period is not observed, as the silver binds to the enzyme active site. After a longer delay (420 seconds), a pH increase is observed. Scale bar = 5 mm.

Details of the study can be found in our paper "communication between hydrogel beads via chemical signalling" which was published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry B (DOI:10.1039/C7TB02278F).

The study forms part of a wider program to develop technology to design hydrogels that can be programmed and communicate. As part of this series we reported earlier in 2017 in Materials Horizons a study on the design of hydrogel fibres and beads with autonomous independent responsive behaviour and have the ability to communicate (DOI: 10.1039/C7MH00033B) and in Journal of Materials Chemistry B technology to program hydrogels.

BonLab develops technology to program hydrogels

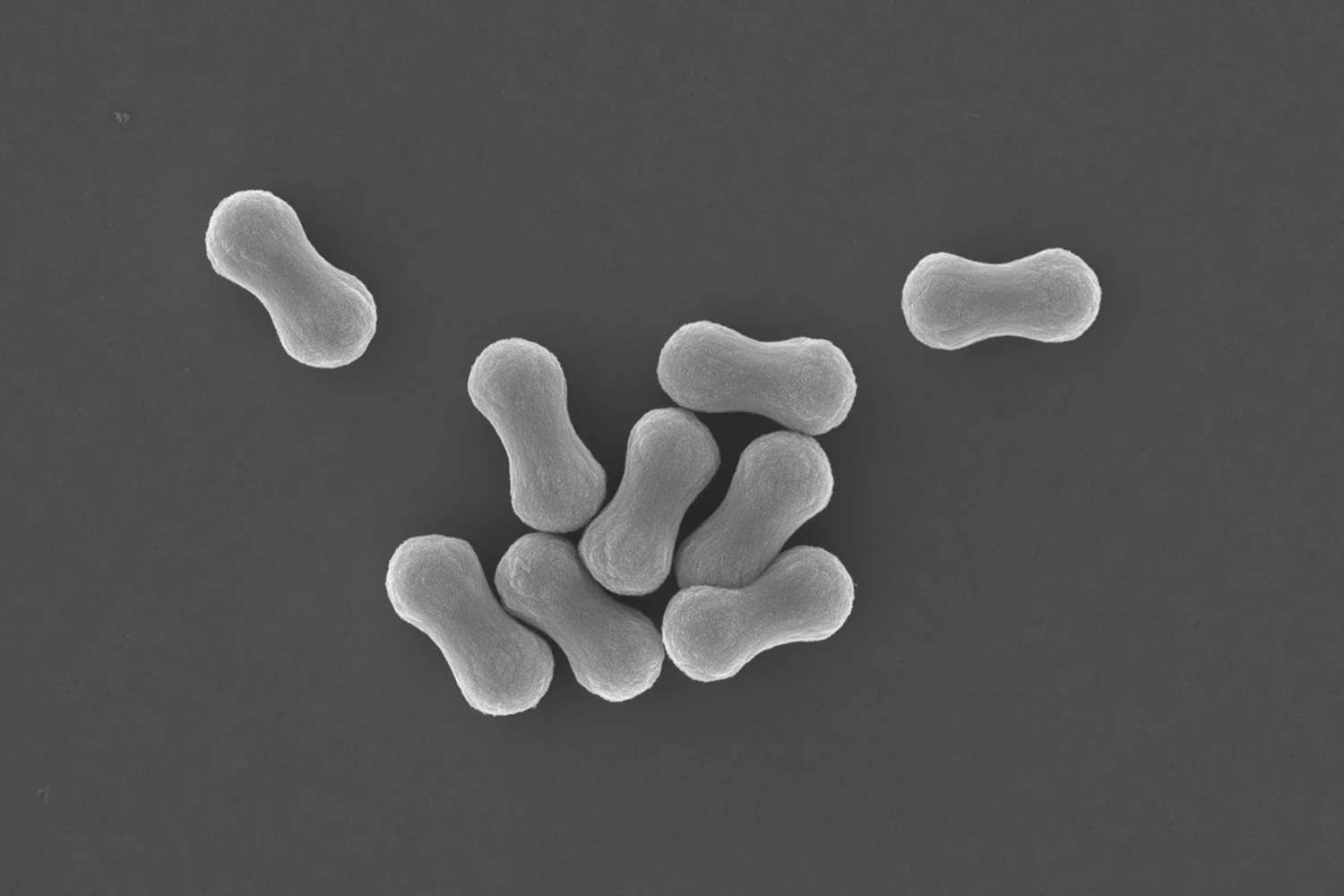

A hydrogel is a solid object predominantly composed of water. The water is held together by a cross-linked 3D mesh, which is formed from components such as polymer molecules or colloidal particles. Hydrogels can be found in a wide range of application areas, for example food (think of agar, gelatine, tapioca, alginate containing products), and health (wound dressing, contact lenses, hygiene products, tissue engineering scaffolds, and drug delivery systems).

In Nature hydrogels can be found widely in soft organisms. Jellyfish spring to mind. These are intriguing creatures and form an inspiration for an area called soft robotics, a discipline seek to fabricate soft structures capable of adaptation, ultimately superseding mechanical hard-robots. Hydrogels are an ideal building block for the design of soft robots as their material characteristics can be tailored. It is however, challenging to introduce and program responsive autonomous behaviour and complex functions into man-made hydrogel objects.

Ross Jaggers and prof.dr.ir. Stefan Bon at BonLab have now developed technology that allows for temporal and spatial programming of hydrogel objects, which we made from the biopolymer sodium alginate. Key to its design was the combined use of enzyme and metal-chelation know-how.

A hydrogel is a solid object predominantly composed of water. The water is held together by a cross-linked 3D mesh, which is formed from components such as polymer molecules or colloidal particles. Hydrogels can be found in a wide range of application areas, for example food (think of agar, gelatine, tapioca, alginate containing products), and health (wound dressing, contact lenses, hygiene products, tissue engineering scaffolds, and drug delivery systems).

In Nature hydrogels can be found widely in soft organisms. Jellyfish spring to mind. These are intriguing creatures and form an inspiration for an area called soft robotics, a discipline seek to fabricate soft structures capable of adaptation, ultimately superseding mechanical hard-robots. Hydrogels are an ideal building block for the design of soft robots as their material characteristics can be tailored. It is however, challenging to introduce and program responsive autonomous behaviour and complex functions into man-made hydrogel objects.

Ross Jaggers and prof.dr.ir. Stefan Bon at BonLab have now developed technology that allows for temporal and spatial programming of hydrogel objects, which we made from the biopolymer sodium alginate. Key to its design was the combined use of enzyme and metal-chelation know-how.

This video shows a programmed hydrogel tree. The hydrogel is made from sodium alginate and cross-linked with Calcium ions. Two scenarios are shown. In a tree of generation 1 the leaves contain a pH sensitive dye and the enzyme urease. The enzyme is trapped into the hydrogel leaves. The tree is floating in water of acidic pH. The water contains urea as trigger/fuel. After a dormant time period the leaves change colour from yellow to blue. This happens as the enzyme decomposes urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide. The bell-shaped activity curve of the enzyme is key to program the time delay in colour change. In a tree of generation 2, the leaves contain emulsion droplets of oil which are coloured red. Again they contain the enzyme urease. In this case, however, the system also contains the compound EDTA, which is a great calcium chelator at higher pH values. After a certain dormant time period, the pH in the leaves rises sufficiently (as a result of the enzymatic reaction decomposing urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide) that EDTA does its job. This results in spatial disintegration of the hydrogel leaves.

This video shows a programmed hydrogel object containing the numbers 1, 2 and 3. The hydrogel is made from sodium alginate and cross-linked with Calcium ions. The numbers contain emulsion droplets of oil which are coloured blue, red and yellow respectively. Each hydrogel number is loaded with a different amount of the enzyme urease. The enzyme is trapped into the gel. Number 1 contains the highest amount, number 3 the lowest. The hydrogel object is floating in water of acidic pH. The water contains urea as trigger/fuel. The system also contains the compound EDTA, which is a great calcium chelator at higher pH values. After a certain programmed dormant time period (dependent on enzyme loading), the pH in each of the numbers rises sufficiently (as a result of the enzymatic reaction decomposing urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide) that EDTA does its job. This results in spatial and temporal disintegration of the numbers.

Details of the study can be found in our paper "temporal and spatial programming in soft composite hydrogel objects" which was published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry B (DOI: 10.1039/C7TB02011B).

The study forms part of a wider program to develop technology to design hydrogels that can be programmed and communicate. As part of this series we reported earlier in 2017 in Materials Horizons a study on the design of hydrogel fibres and beads with autonomous independent responsive behaviour and have the ability to communicate (DOI: 10.1039/C7MH00033B).