BONLAB BLOG

Thoughts

&

Scientific Fiction

BonLab develops technology to program hydrogels

A hydrogel is a solid object predominantly composed of water. The water is held together by a cross-linked 3D mesh, which is formed from components such as polymer molecules or colloidal particles. Hydrogels can be found in a wide range of application areas, for example food (think of agar, gelatine, tapioca, alginate containing products), and health (wound dressing, contact lenses, hygiene products, tissue engineering scaffolds, and drug delivery systems).

In Nature hydrogels can be found widely in soft organisms. Jellyfish spring to mind. These are intriguing creatures and form an inspiration for an area called soft robotics, a discipline seek to fabricate soft structures capable of adaptation, ultimately superseding mechanical hard-robots. Hydrogels are an ideal building block for the design of soft robots as their material characteristics can be tailored. It is however, challenging to introduce and program responsive autonomous behaviour and complex functions into man-made hydrogel objects.

Ross Jaggers and prof.dr.ir. Stefan Bon at BonLab have now developed technology that allows for temporal and spatial programming of hydrogel objects, which we made from the biopolymer sodium alginate. Key to its design was the combined use of enzyme and metal-chelation know-how.

A hydrogel is a solid object predominantly composed of water. The water is held together by a cross-linked 3D mesh, which is formed from components such as polymer molecules or colloidal particles. Hydrogels can be found in a wide range of application areas, for example food (think of agar, gelatine, tapioca, alginate containing products), and health (wound dressing, contact lenses, hygiene products, tissue engineering scaffolds, and drug delivery systems).

In Nature hydrogels can be found widely in soft organisms. Jellyfish spring to mind. These are intriguing creatures and form an inspiration for an area called soft robotics, a discipline seek to fabricate soft structures capable of adaptation, ultimately superseding mechanical hard-robots. Hydrogels are an ideal building block for the design of soft robots as their material characteristics can be tailored. It is however, challenging to introduce and program responsive autonomous behaviour and complex functions into man-made hydrogel objects.

Ross Jaggers and prof.dr.ir. Stefan Bon at BonLab have now developed technology that allows for temporal and spatial programming of hydrogel objects, which we made from the biopolymer sodium alginate. Key to its design was the combined use of enzyme and metal-chelation know-how.

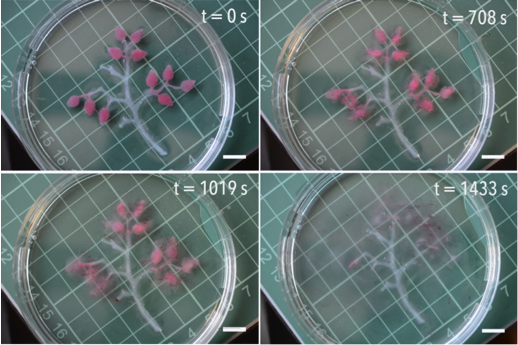

This video shows a programmed hydrogel tree. The hydrogel is made from sodium alginate and cross-linked with Calcium ions. Two scenarios are shown. In a tree of generation 1 the leaves contain a pH sensitive dye and the enzyme urease. The enzyme is trapped into the hydrogel leaves. The tree is floating in water of acidic pH. The water contains urea as trigger/fuel. After a dormant time period the leaves change colour from yellow to blue. This happens as the enzyme decomposes urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide. The bell-shaped activity curve of the enzyme is key to program the time delay in colour change. In a tree of generation 2, the leaves contain emulsion droplets of oil which are coloured red. Again they contain the enzyme urease. In this case, however, the system also contains the compound EDTA, which is a great calcium chelator at higher pH values. After a certain dormant time period, the pH in the leaves rises sufficiently (as a result of the enzymatic reaction decomposing urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide) that EDTA does its job. This results in spatial disintegration of the hydrogel leaves.

This video shows a programmed hydrogel object containing the numbers 1, 2 and 3. The hydrogel is made from sodium alginate and cross-linked with Calcium ions. The numbers contain emulsion droplets of oil which are coloured blue, red and yellow respectively. Each hydrogel number is loaded with a different amount of the enzyme urease. The enzyme is trapped into the gel. Number 1 contains the highest amount, number 3 the lowest. The hydrogel object is floating in water of acidic pH. The water contains urea as trigger/fuel. The system also contains the compound EDTA, which is a great calcium chelator at higher pH values. After a certain programmed dormant time period (dependent on enzyme loading), the pH in each of the numbers rises sufficiently (as a result of the enzymatic reaction decomposing urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide) that EDTA does its job. This results in spatial and temporal disintegration of the numbers.

Details of the study can be found in our paper "temporal and spatial programming in soft composite hydrogel objects" which was published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry B (DOI: 10.1039/C7TB02011B).

The study forms part of a wider program to develop technology to design hydrogels that can be programmed and communicate. As part of this series we reported earlier in 2017 in Materials Horizons a study on the design of hydrogel fibres and beads with autonomous independent responsive behaviour and have the ability to communicate (DOI: 10.1039/C7MH00033B).

Roughening up polymer microspheres and their diffusion in a liquid

Spherical microparticles that are roughened up, so that their surfaces are no longer smooth, are intriguing. You can wonder that when we place a large number of these particles in a liquid, it may show interesting rheological behaviour. For example, would they behave like cornstarch in that when we apply a lot of shear it thickens? You can imagine that spiky spheres can interlock and jam. Biologists are interested in how microparticles interact with cells and organisms, and have started to show that the shape of the particle can play an important role. Similarly, these small particles of intricate shape may show fascinating behavior at deformable surfaces, for example is there a cheerio effect?, and may show unexpected motion. This sounds all fun, but how do we make rough microparticles, as for polymer ones this is not easy?

Spherical microparticles that are roughened up, so that their surfaces are no longer smooth, are intriguing. You can wonder that when we place a large number of these particles in a liquid, it may show interesting rheological behaviour. For example, would they behave like cornstarch in that when we apply a lot of shear it thickens? You can imagine that spiky spheres can interlock and jam. Biologists are interested in how microparticles interact with cells and organisms, and have started to show that the shape of the particle can play an important role. Similarly, these small particles of intricate shape may show fascinating behavior at deformable surfaces, for example is there a cheerio effect?, and may show unexpected motion. This sounds all fun, but how do we make rough microparticles, as for polymer ones this is not easy?

Fig. 1 Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of poly(styrene) microspheres deformed at 110 °C within a dried colloidal inorganic matrix for approximate time periods of 10, 30, 60 and 120 min (a–d), (e–h), (i–l). The inorganic particles utilized were cigar-shaped calcium carbonate (a–d), large, rod-shaped calcium carbonate (e–h) and small, spherical/oblong-shaped zinc oxide (i–l). Scale bars = 1.0 μm.

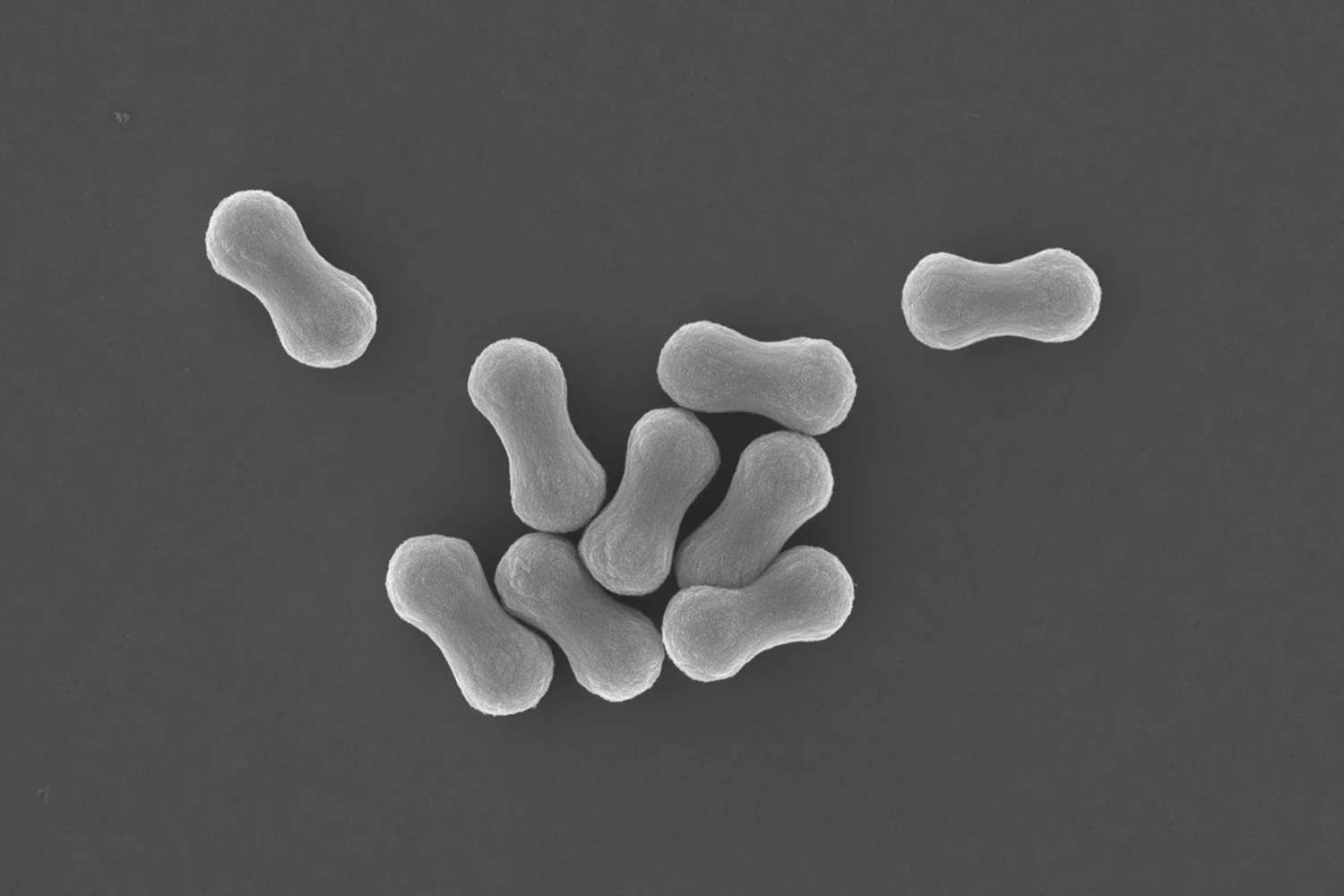

In our paper published in Soft Matter we report an easy and versatile method to morph spherical microparticles into their rough surface textured analogues. For this, we embed the particles into an inorganic matrix of intricate shape and heat them up above the temperature at which the particles become a polymer melt. Capillary imbibition imprints the inorganic texture into the particles, turning them rough. We also look at how the particles move through a liquid, by tracking their motional behavior. Rough particles appear bigger, than their smooth precursors.

You can read the paper here: DOI:10.1039/C7SM00589J

A mechanistic investigation of Pickering emulsion polymerization

Emulsion polymerization is an important industrial production method to prepare latexes. Polymer latex particles are typically 40-1000 nm and dispersed in water. The polymer dispersions find application in wide ranges of products, such as coatings and adhesives, gloves and condoms, paper textiles and carpets, concrete reinforcement, and so on.

Conventional emulsion polymerization processes make use of molecular surfactants, which aids the polymerization reaction during which the particles are made and keeps the polymer colloids dispersed in water. We, and others, introduced Pickering emulsion polymerization a decade ago in which we replace common surfactants with inorganic nanoparticles.

In Pickering emulsion polymerization the polymer particles made are covered with an armor of the inorganic nanoparticles. This offers a nanocomposite colloid which may have intriguing properties and features not present in conventional "naked" polymer latexes.

To fully exploit this innovation in emulsion polymers, a mechanistic understanding of the polymerization process is essential. Current understanding is limited which restricts the use of the technique in the fabrication of more complex, multilayered colloids.

Emulsion polymerization is an important industrial production method to prepare latexes. Polymer latex particles are typically 40-1000 nm and dispersed in water. The polymer dispersions find application in wide ranges of products, such as coatings and adhesives, gloves and condoms, paper textiles and carpets, concrete reinforcement, and so on.

Conventional emulsion polymerization processes make use of molecular surfactants, which aids the polymerization reaction during which the particles are made and keeps the polymer colloids dispersed in water. We, and others, introduced Pickering emulsion polymerization a decade ago in which we replace common surfactants with inorganic nanoparticles.

In Pickering emulsion polymerization the polymer particles made are covered with an armor of the inorganic nanoparticles. This offers a nanocomposite colloid which may have intriguing properties and features not present in conventional "naked" polymer latexes.

To fully exploit this innovation in emulsion polymers, a mechanistic understanding of the polymerization process is essential. Current understanding is limited which restricts the use of the technique in the fabrication of more complex, multilayered colloids.

In our paper, recently published in Polymer Chemistry, clarity is provided through an in-depth investigation into the Pickering emulsion polymerization of methyl methacrylate (MMA) in the presence of nano-sized colloidal silica (Ludox TM-40). Mechanistic insights are discussed by studying both the adsorption of the stabiliser to the surface of the latex particles and polymerization kinetics. The adhesion of the Pickering nanoparticles was found not to be spontaneous, as confirmed by cryo-TEM analysis of MMA droplets in water and monomer-swollen PMMA latexes. This supports the theory that the inorganic particles are driven towards the interface as a result of a heterocoagulation event in the water phase with a growing oligoradical. The emulsion polymerizations were monitored by reaction calorimetry in order to establish accurate values for monomer conversion and the overall rate of polymerizations (Rp). Rp increased for higher initial silica concentrations and the polymerizations were found to follow pseudo-bulk kinetics.

The paper can be read here: http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/C7PY00308K