BONLAB BLOG

Thoughts

&

Scientific Fiction

BonLab does PISA with RAFT-agent version 0.1

Call them plastics, polymers, elastomers, thermoplasts, thermosets, or macromolecules. What’s in the name? Despite the current negative press in view of considerable environmental concerns on how we deal with polymer materials post-use, it cannot be denied that polymers have been a catalyst in the evolution of human society in the 20st century, and continue to do so.

One of the synthetic pathways toward polymer molecules is free radical polymerization, a process known since the late 1800s and conceptually developed from the 1920s-1930s onwards. Since the 1980s it gradually became possible to tailor the chemical composition and chain architecture of a macromolecule. The process is called reversible deactivation radical polymerization (RDRP), also known as controlled or living radical polymerization. By grabbing control on how individual polymer chains are made, with the ability to control the sequencing of its building blocks, known as monomers, true man-made design of large functional molecules has become reality. This architectural control of polymer molecules allows for materials to be formulated with unprecedented physical and mechanical properties.

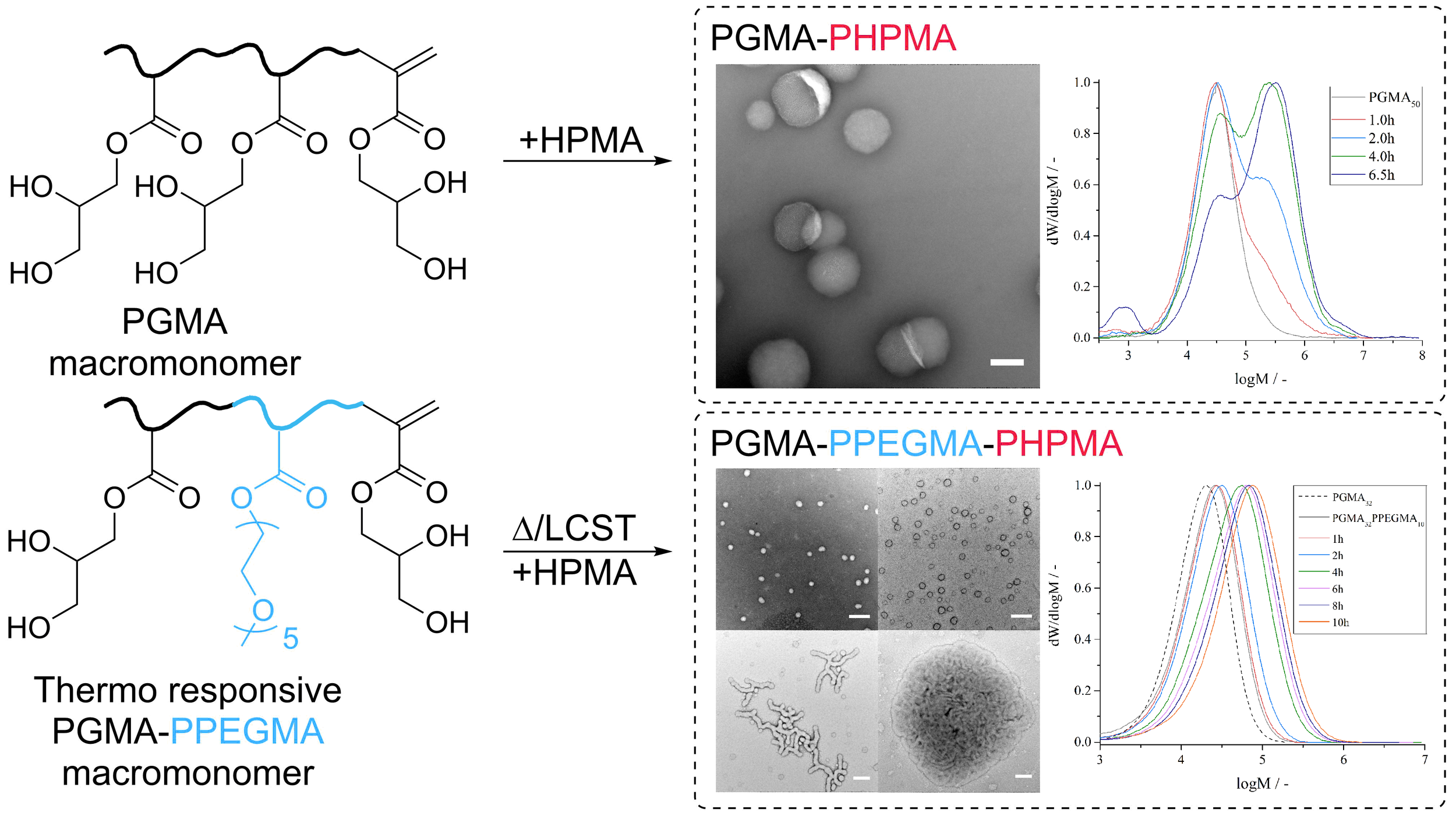

One interesting phenomenon is that when we carry out an RDRP reaction using a “living” polymer (a first block) dissolved in for example water and try to extend the macromolecule by growing a second block that does not dissolve in water, it is possible to arrange the blockcopolymer molecules by grouping them together into a variety of small (colloidal) structures dispersed in water. More interestingly, these assembled suprastructures have the ability to dynamically change shape throughout the polymerization process, for example to transform from spherical, to cylindrical, to vesicle type objects. This Polymerization Induced Self-Assembly process has been given the acronym PISA.

Call them plastics, polymers, elastomers, thermoplasts, thermosets, or macromolecules. What’s in the name? Despite the current negative press in view of considerable environmental concerns on how we deal with polymer materials post-use, it cannot be denied that polymers have been a catalyst in the evolution of human society in the 20st century, and continue to do so.

One of the synthetic pathways toward polymer molecules is free radical polymerization, a process known since the late 1800s and conceptually developed from the 1920s-1930s onwards. Since the 1980s it gradually became possible to tailor the chemical composition and chain architecture of a macromolecule. The process is called reversible deactivation radical polymerization (RDRP), also known as controlled or living radical polymerization. By grabbing control on how individual polymer chains are made, with the ability to control the sequencing of its building blocks, known as monomers, true man-made design of large functional molecules has become reality. This architectural control of polymer molecules allows for materials to be formulated with unprecedented physical and mechanical properties.

One interesting phenomenon is that when we carry out an RDRP reaction using a “living” polymer (a first block) dissolved in for example water and try to extend the macromolecule by growing a second block that does not dissolve in water, it is possible to arrange the blockcopolymer molecules by grouping them together into a variety of small (colloidal) structures dispersed in water. More interestingly, these assembled suprastructures have the ability to dynamically change shape throughout the polymerization process, for example to transform from spherical, to cylindrical, to vesicle type objects. This Polymerization Induced Self-Assembly process has been given the acronym PISA.

One way to carry out the synthesis of macromolecules by reversible deactivation radical polymerization is to make use of the concept of Reversible Addition-Fragmentation chain-Transfer, known as RAFT. This polymerization process has conventionally now uses sulfur-chemistry in the synthesis of RAFT-agents (versions 1.0 and up so to say), which efficiently controlled the growth of macromolecules. It is based on an invention from the mid 1990s, but more interestingly came to fruition by the realization that methacrylate-based macromonomers acted as RAFT-agents (here version 0.1). These latter compounds were, however, not very efficient, and abandoned.

We now show in the BonLab’s latest paper published in ACS Macro Letters that methacrylate-based macromonomers can be used successfully as RAFT-agents in Polymerization Induced Self-Assembly (PISA) processes by carefully considering the mechanistic aspects.

Prof.dr.ir. Stefan Bon says: “Our team is delighted with the results and we are happy the paper features in ACS Macro Letters. RAFT-ing the classic way will for sure get more than a 2nd try! To show that PISA with version 0.1 RAFT-agents is indeed possible, was an excellent team effort by PhD researcher Andrea Lotierzo, and 2nd year undergraduate Warwick Chemistry student (now 3rd year) Ryan Schofield.”

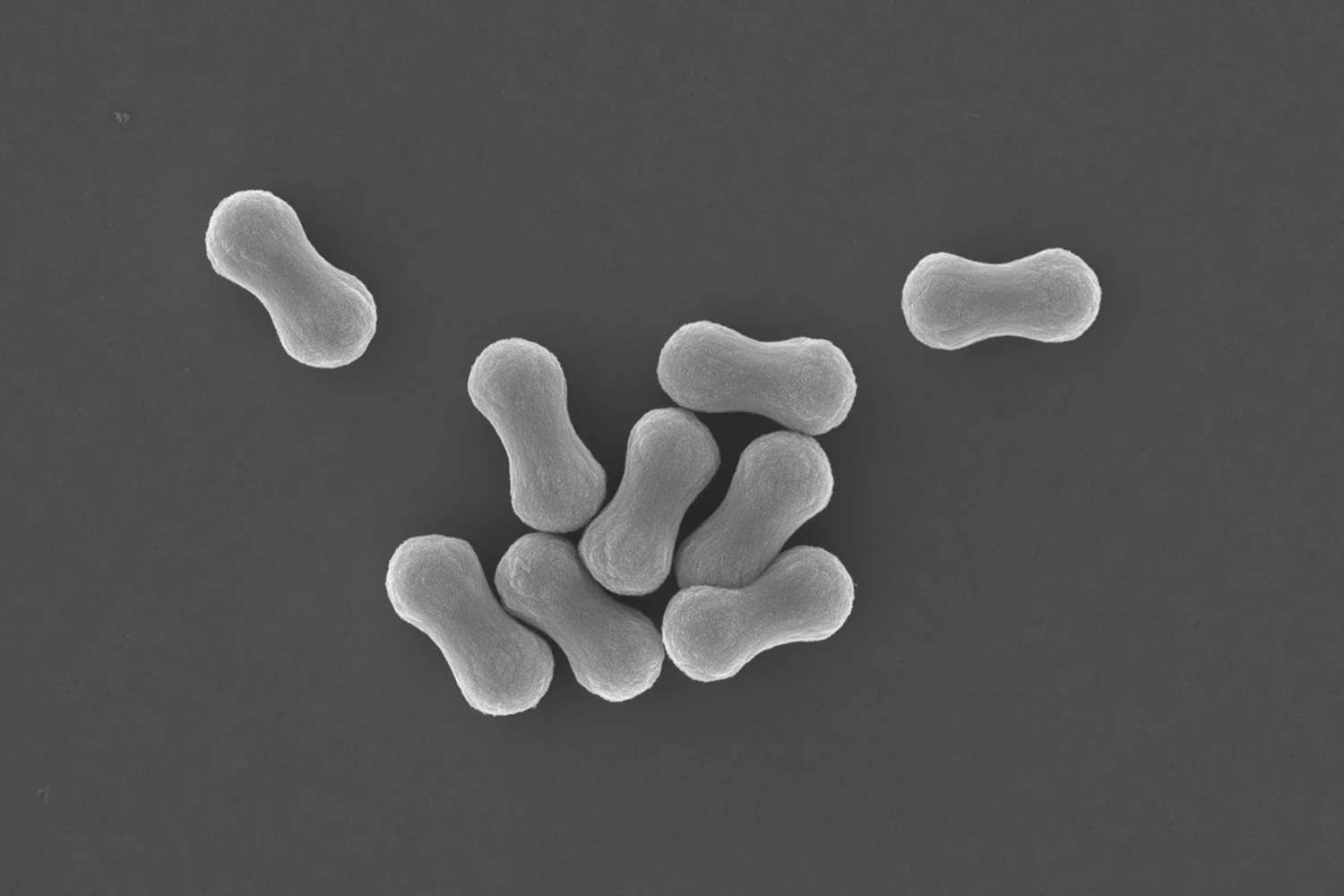

The use of this class of "primitive" RAFT-agents in heterogeneous polymerizations is however not trivial, because of their inherent low reactivity. In our work we demonstrate that two obstacles need to be overcome, one being control of chain-growth (propagation), the other monomer partitioning. Batch dispersion polymerizations of hydroxypropyl methacrylate in presence of poly(glycerol methacrylate) macromonomers in water showed limited control of chain-growth. Semi-continuous experiments whereby monomer was fed improved results only to some extent. Control of propagation is essential for PISA to allow for dynamic rearrangement of colloidal structures. We tackled the problem of monomer partitioning (caused by uncontrolled particle nucleation) by starting the polymerization with an amphiphilic thermo-responsive diblock copolymer, already “phase-separated” from solution. TEM analysis showed that PISA was successful and that different consecutive particle morphologies were obtained throughout the polymerization process.

The paper can be downloaded from ACS Macro Letters. DOI: 10.1021/acsmacrolett.7b00857

BonLab makes hydrogel beads communicate

Hydrogels are soft objects that are mainly composed of water. The water is held together by a 3D cross-linked mesh. In our latest work we show that hydrogel beads made from the bio-sustainable polymer alginate can be loaded up with different types of molecules so that the beads can communicate via chemistry.

Chemical communication underpins a plethora of biological functions and behaviours. Plants, animals and insects rely on it for cooperative action, your body uses it to moderate its internal environment and your cells require it to survive.

A key goal of materials science is to mimic this biological behaviour, and synthetic objects that are able to communicate with one another by the sending and receiving of chemical messengers are of great interest at a range of length scales. The most widely explored platform for this kind of communication is between nanoparticles, and to a lesser extent, vesicles, but to date, very little work explores communication between large (millimetre-sized), soft objects, such as hydrogels.

In our work published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry B, we present combinations of large, soft hydrogel objects containing different signalling and receiving molecules, can exchange chemical signals. Beads encapsulating one of three species, namely the enzyme urease, the enzyme inhibitor silver (Ag+), or the Ag+ chelator dithiothreitol (DTT), are shown to interact when placed in contact with one another. By exploiting the interplay between the enzyme, its reversible inhibitor, and this inhibitor’s chelator, we demonstrate a series of ‘conversations’ between the beads.

Hydrogels are soft objects that are mainly composed of water. The water is held together by a 3D cross-linked mesh. In our latest work we show that hydrogel beads made from the bio-sustainable polymer alginate can be loaded up with different types of molecules so that the beads can communicate via chemistry.

Chemical communication underpins a plethora of biological functions and behaviours. Plants, animals and insects rely on it for cooperative action, your body uses it to moderate its internal environment and your cells require it to survive.

A key goal of materials science is to mimic this biological behaviour, and synthetic objects that are able to communicate with one another by the sending and receiving of chemical messengers are of great interest at a range of length scales. The most widely explored platform for this kind of communication is between nanoparticles, and to a lesser extent, vesicles, but to date, very little work explores communication between large (millimetre-sized), soft objects, such as hydrogels.

In our work published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry B, we present combinations of large, soft hydrogel objects containing different signalling and receiving molecules, can exchange chemical signals. Beads encapsulating one of three species, namely the enzyme urease, the enzyme inhibitor silver (Ag+), or the Ag+ chelator dithiothreitol (DTT), are shown to interact when placed in contact with one another. By exploiting the interplay between the enzyme, its reversible inhibitor, and this inhibitor’s chelator, we demonstrate a series of ‘conversations’ between the beads.

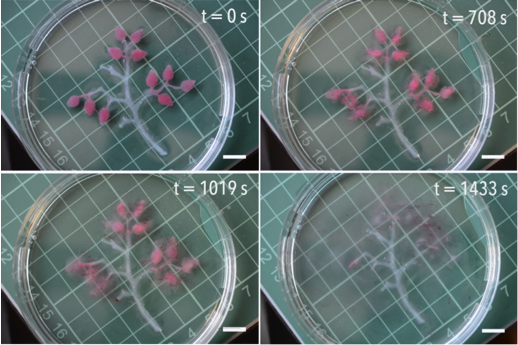

The movie shows two different scenario's:

Scenario 1: When a bead containing both urease, at a concentration of 5 g/L, and silver, at a concentration of 0.2 mmol/L, is immersed in a 0.1 mol/L solution of urea, no pH increase is observed (left bead). If an identical bead (middle bead) makes contact with one containing 0.52 mol/L DTT (right bead), the contained DTT diffuses into the silver-bound ‘enzyme’ bead. This results in the chelation of silver ions from the urease and thus its reactivation. Scale bar = 5 mm.

Scenario 2: a 1 mmol/L ‘silver’ bead sits next to a 0.125 g/L ‘urease’ bead (far left and the top middle bead, respectively) in an aqueous solution of 0.1 mol/L urea. In this case, however, a third bead is introduced, namely a 0.52 mol/L ‘DTT’ bead (bottom middle). The far-right bead, containing 0.125 g/L urease, undergoes its colour and pH change as expected (onset at 214 seconds). As the left-hand ‘enzyme’ bead makes contact with a ‘silver’ bead, a pH increase after this time period is not observed, as the silver binds to the enzyme active site. After a longer delay (420 seconds), a pH increase is observed. Scale bar = 5 mm.

Details of the study can be found in our paper "communication between hydrogel beads via chemical signalling" which was published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry B (DOI:10.1039/C7TB02278F).

The study forms part of a wider program to develop technology to design hydrogels that can be programmed and communicate. As part of this series we reported earlier in 2017 in Materials Horizons a study on the design of hydrogel fibres and beads with autonomous independent responsive behaviour and have the ability to communicate (DOI: 10.1039/C7MH00033B) and in Journal of Materials Chemistry B technology to program hydrogels.

BonLab develops technology to program hydrogels

A hydrogel is a solid object predominantly composed of water. The water is held together by a cross-linked 3D mesh, which is formed from components such as polymer molecules or colloidal particles. Hydrogels can be found in a wide range of application areas, for example food (think of agar, gelatine, tapioca, alginate containing products), and health (wound dressing, contact lenses, hygiene products, tissue engineering scaffolds, and drug delivery systems).

In Nature hydrogels can be found widely in soft organisms. Jellyfish spring to mind. These are intriguing creatures and form an inspiration for an area called soft robotics, a discipline seek to fabricate soft structures capable of adaptation, ultimately superseding mechanical hard-robots. Hydrogels are an ideal building block for the design of soft robots as their material characteristics can be tailored. It is however, challenging to introduce and program responsive autonomous behaviour and complex functions into man-made hydrogel objects.

Ross Jaggers and prof.dr.ir. Stefan Bon at BonLab have now developed technology that allows for temporal and spatial programming of hydrogel objects, which we made from the biopolymer sodium alginate. Key to its design was the combined use of enzyme and metal-chelation know-how.

A hydrogel is a solid object predominantly composed of water. The water is held together by a cross-linked 3D mesh, which is formed from components such as polymer molecules or colloidal particles. Hydrogels can be found in a wide range of application areas, for example food (think of agar, gelatine, tapioca, alginate containing products), and health (wound dressing, contact lenses, hygiene products, tissue engineering scaffolds, and drug delivery systems).

In Nature hydrogels can be found widely in soft organisms. Jellyfish spring to mind. These are intriguing creatures and form an inspiration for an area called soft robotics, a discipline seek to fabricate soft structures capable of adaptation, ultimately superseding mechanical hard-robots. Hydrogels are an ideal building block for the design of soft robots as their material characteristics can be tailored. It is however, challenging to introduce and program responsive autonomous behaviour and complex functions into man-made hydrogel objects.

Ross Jaggers and prof.dr.ir. Stefan Bon at BonLab have now developed technology that allows for temporal and spatial programming of hydrogel objects, which we made from the biopolymer sodium alginate. Key to its design was the combined use of enzyme and metal-chelation know-how.

This video shows a programmed hydrogel tree. The hydrogel is made from sodium alginate and cross-linked with Calcium ions. Two scenarios are shown. In a tree of generation 1 the leaves contain a pH sensitive dye and the enzyme urease. The enzyme is trapped into the hydrogel leaves. The tree is floating in water of acidic pH. The water contains urea as trigger/fuel. After a dormant time period the leaves change colour from yellow to blue. This happens as the enzyme decomposes urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide. The bell-shaped activity curve of the enzyme is key to program the time delay in colour change. In a tree of generation 2, the leaves contain emulsion droplets of oil which are coloured red. Again they contain the enzyme urease. In this case, however, the system also contains the compound EDTA, which is a great calcium chelator at higher pH values. After a certain dormant time period, the pH in the leaves rises sufficiently (as a result of the enzymatic reaction decomposing urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide) that EDTA does its job. This results in spatial disintegration of the hydrogel leaves.

This video shows a programmed hydrogel object containing the numbers 1, 2 and 3. The hydrogel is made from sodium alginate and cross-linked with Calcium ions. The numbers contain emulsion droplets of oil which are coloured blue, red and yellow respectively. Each hydrogel number is loaded with a different amount of the enzyme urease. The enzyme is trapped into the gel. Number 1 contains the highest amount, number 3 the lowest. The hydrogel object is floating in water of acidic pH. The water contains urea as trigger/fuel. The system also contains the compound EDTA, which is a great calcium chelator at higher pH values. After a certain programmed dormant time period (dependent on enzyme loading), the pH in each of the numbers rises sufficiently (as a result of the enzymatic reaction decomposing urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide) that EDTA does its job. This results in spatial and temporal disintegration of the numbers.

Details of the study can be found in our paper "temporal and spatial programming in soft composite hydrogel objects" which was published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry B (DOI: 10.1039/C7TB02011B).

The study forms part of a wider program to develop technology to design hydrogels that can be programmed and communicate. As part of this series we reported earlier in 2017 in Materials Horizons a study on the design of hydrogel fibres and beads with autonomous independent responsive behaviour and have the ability to communicate (DOI: 10.1039/C7MH00033B).